I. Introduction – A Birthday Worth Remembering

On July 10, 1509, in the small cathedral town of Noyon, France, a child was born who would grow to become one of the most influential theologians and church reformers in the history of Christianity—John Calvin. Though his life would be marked by exile, controversy, and sickness, Calvin’s relentless pursuit of God’s truth would shape not only the course of the Protestant Reformation, but also the worship, polity, and doctrine of countless churches around the world. On the anniversary of his birth, we do well to pause, not to glorify the man, but to give thanks to God for the ways He used a humble scholar from northern France to ignite theological clarity and spiritual renewal that still resonates centuries later.

Calvin’s theological system is best known through his magnum opus, The Institutes of the Christian Religion—a work that he first published at the age of 26 and continued to revise throughout his life until the definitive edition of 1559. But Calvin was more than a theologian; he was a pastor, a biblical commentator, and above all, a servant of Christ’s church. He insisted that theology must never be abstract but always devotional and practical: “True and sound wisdom consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves” (Battles ed., Institutes, 1.1.1). This reciprocal knowledge—of who God is and who we are in relation to Him—forms the heartbeat of Calvin’s spiritual vision.

Even in the opening lines of the Institutes, Calvin displays a deep humility before the majesty of God. “Without knowledge of self,” he writes, “there is no knowledge of God” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 1.1.1). Yet he is quick to reverse the mirror: “It is evident that man never attains to a true self-knowledge until he has previously contemplated the face of God, and come down after such contemplation to look into himself” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 1.1.2). For Calvin, the knowledge of God is not a cold academic pursuit, but a furnace that refines and humbles. We behold the holiness of God, and then see how stained and needy we are in contrast.

Calvin’s theology is often misrepresented as dry, distant, and austere. Yet those who take time to read him will encounter someone deeply committed to the warmth of divine love and the assurance of God’s grace. Calvin writes, “Our being should not be under the dominion of ourselves, but we should live entirely to the Lord and die to him” (Battles ed., Institutes, 3.7.1). From this, the Christian life becomes not a rigid checklist of doctrine, but a responsive life of joyful obedience rooted in love for God.

His pastoral vision extended far beyond academic theology. Calvin spent his life building up the church in Geneva, despite multiple exiles, illnesses, and opposition. He preached sermons daily, taught students, visited the sick, and labored for the moral and spiritual renewal of the city. One of his most powerful legacies is not just what he taught, but how he lived under the Lordship of Christ. “We are not our own,” he writes, “therefore, let us live for him and die for him” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 3.7.1).

And yet, Calvin’s own awareness of human weakness and divine sovereignty kept him grounded. He described the human heart as “a perpetual forge of idols” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 1.11.8) and pointed readers constantly away from their own works to rest in the finished work of Christ. “Until men recognize that they owe everything to God,” he writes, “that they are nourished by his fatherly care, that he is the Author of their every good—until they humble themselves completely and strip themselves of all self-confidence—they will never give him his due” (Battles ed., Institutes, 1.1.1).

So, on this July 10th, we remember John Calvin not as a flawless man or a distant intellectual, but as a faithful servant of Christ who labored so that others might see the greatness of God. As he once prayed, “I offer my heart to you, O Lord, promptly and sincerely.” That motto—Cor meum tibi offero, Domine, prompte et sincere—still echoes today. May his life invite us to deeper reverence, humility, and faith in our sovereign and gracious God.

II. Calvin the Theologian: Institutes and a Vision of God’s Glory

If Martin Luther cracked open the door of the Reformation, John Calvin stepped through it and built a theological house to dwell in. His Institutes of the Christian Religion is not only the most influential Reformed work of systematic theology, but one of the most enduring and expansive theological texts in the history of the church. Written originally in 1536 and revised over two decades until its final form in 1559, the Institutes was Calvin’s attempt to give “a sum of piety” and a “doctrine that is necessary to know” (Battles ed., Prefatory Address). It was, in Calvin’s words, “a key to open a way for all children of God into a right and true understanding of Holy Scripture” (Beveridge ed., Prefatory Address).

From the first page to the last, Calvin’s theology revolves around one central aim: the glory of God in the salvation of sinners. The famous opening lines declare that “true and sound wisdom consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves” (Battles ed., Institutes, 1.1.1). This twofold knowledge sets the framework for everything that follows. God is sovereign, holy, and utterly self-sufficient; man is fallen, needy, and dependent. Theology, then, is not an abstract science, but a practical discipline meant to drive the heart into awe, reverence, and trust.

Calvin’s emphasis on the sovereignty of God is one of the defining marks of his theology. This does not begin with the controversial doctrine of predestination, but with the very nature of God as Creator and Sustainer of all things. “Nothing is more absurd,” Calvin writes, “than that anything should be done without God’s ordination, because it happens against his will” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 1.16.6). Providence is not a cold determinism, but the comforting assurance that not even a sparrow falls apart from the Father’s hand.

In matters of salvation, Calvin’s theological clarity is most vibrant. He saw man as spiritually dead apart from grace, incapable of seeking God or choosing righteousness on his own. “Original sin,” Calvin writes, “seems to be a hereditary depravity and corruption of our nature” which renders us “obnoxious to God’s wrath” (Battles ed., Institutes, 2.1.8). Yet it is in this helpless state that the mercy of God shines brightest. Election, for Calvin, is not a theological abstraction but a testimony of divine love: “God has adopted us once for all in order that we may persevere to the end” (Battles ed., Institutes, 3.21.7).

Calvin’s doctrine of union with Christ brings warmth and cohesion to his soteriology. Every saving benefit—justification, sanctification, adoption—is received in Christ and through the Spirit. “As long as Christ remains outside of us,” Calvin insists, “and we are separated from him, all that he has suffered and done for the salvation of the human race remains useless and of no value to us” (Battles ed., Institutes, 3.1.1). Faith is the Spirit-given bond that unites the believer to Christ, and this union is both legal (justification) and transformative (sanctification).

Far from promoting a dry orthodoxy, Calvin taught that true theology always issues in piety, which he defined as “that reverence joined with love of God which the knowledge of his benefits induces” (Battles ed., Institutes, 1.2.1). The goal of doctrine is not simply to inform but to ignite the heart. Theology is not merely for the scholar but for the worshiper. “It is evident,” Calvin writes, “that man never attains to a true self-knowledge until he has previously contemplated the face of God” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 1.1.2). To know God rightly is to be changed by Him inwardly.

The scope of the Institutes is enormous—covering topics from Scripture’s authority, to the Trinity, to civil government—but it is always tethered to one central concern: that God be honored and glorified, and that sinners find refuge in Christ. Whether Calvin is describing the majesty of God’s law or the depths of the atonement, he writes with a pastor’s heart and a theologian’s mind. He leaves no room for self-confidence, but points again and again to the sufficiency of Christ and the majesty of grace.

In a world often intoxicated with autonomy and self-justification, Calvin’s vision remains radically God-centered. “Man is so blinded by pride,” he writes, “that he counts himself sufficient to obtain righteousness” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 3.12.2). But Calvin knew better, and he called the church to look upward—to the sovereign God, to the crucified Christ, to the Spirit who gives life. That vision, born in the pages of the Institutes, still gives light to pilgrims who long to see the face of God.

III. Calvin’s Ecclesiology: A Church Reformed and Always Reforming

For John Calvin, the doctrine of the church was not an afterthought but a vital branch of Christian theology. He believed that God’s redemptive work in the world was not merely individual but corporate—centered in the visible body of Christ, the church militant on earth. As one who labored tirelessly for ecclesiastical reform in Geneva, Calvin saw the reformation of the church as the necessary outworking of the gospel’s renewal. The purified preaching of the Word and the right administration of the sacraments were, for him, not just ecclesial duties—they were marks of the true church.

Calvin famously defined the church in these terms:

“Wherever we see the word of God purely preached and heard, and the sacraments administered according to Christ’s institution, there, it is not to be doubted, a church of God exists.” (Battles ed., Institutes, 4.1.9)

This twofold standard—Word and sacrament—was Calvin’s measuring rod for authentic Christian community. He rejected both the spiritual individualism that severed Christians from the visible church and the corrupted institutionalism of the medieval church, which had obscured the gospel with superstition and abuse. In Geneva, he sought to restore the church to biblical fidelity, not by innovation, but by recovery—a return to apostolic simplicity and purity.

One of Calvin’s most significant contributions to ecclesiology was his reformation of church government. He taught that Christ alone is the Head of the church, and under Him are four offices established for its upbuilding: pastors, teachers (doctors), elders, and deacons. These roles were grounded in Scripture, particularly in Ephesians 4 and 1 Timothy 3. Calvin resisted any form of hierarchy that elevated one office above the rest—especially the monarchical papacy—calling it a “tyranny” inconsistent with the New Testament church.

“There is no other rule for the right government of the church than that which he [Christ] has laid down in his word.” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 4.8.9)

The pastors were responsible for preaching and administering the sacraments; the teachers ensured doctrinal integrity; the elders oversaw the moral and spiritual conduct of the flock; and the deacons cared for the poor and needy. Calvin’s Geneva Consistory, made up of pastors and elders, exercised church discipline, not to tyrannize consciences, but to maintain the holiness of the church and shepherd straying sheep back to Christ.

Church discipline, in Calvin’s view, was not optional but essential. He wrote:

“As the saving doctrine of Christ is the soul of the church, so discipline forms the ligaments which connect the members together, and keep each in its proper place.” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 4.12.1)

He understood discipline as both corrective and restorative—an expression of love, not legalism. A church that failed to practice discipline would, in Calvin’s mind, quickly become spiritually diseased and indistinguishable from the world. “Discipline,” he warned, “is like a bridle to restrain and tame those who rage against the doctrine of Christ” (Battles ed., Institutes, 4.12.1).

The Lord’s Supper, too, held a central place in Calvin’s ecclesiology. While rejecting Roman transubstantiation and Lutheran consubstantiation, Calvin taught that believers are truly nourished by the real spiritual presence of Christ through faith. The Supper is not a bare symbol, but a means of grace, binding the church together in union with Christ. As Calvin wrote:

“The sacred mystery of the Supper consists in the spiritual reality of that communion which we have with Christ in his flesh and blood, and with all his members.” (Battles ed., Institutes, 4.17.1)

For Calvin, the visible church was not perfect, but it was necessary. “The church is the mother of all believers,” he declared, “for there is no other way to enter into life unless she conceive us in her womb, give us birth, nourish us at her breast, and lastly…keep us under her care and guidance” (Battles ed., Institutes, 4.1.4). Though plagued with faults, the church remains God’s chosen instrument to proclaim the gospel, train disciples, and extend the kingdom.

This ecclesiological vision became foundational to Presbyterian polity and Reformed churches worldwide. Its genius was in balancing local authority with biblical accountability, structure with spiritual vitality. Calvin’s model aimed to recover not just doctrinal purity, but also pastoral care and community holiness—reforming the church according to the Word of God.

In our fragmented age, Calvin’s vision is a call to recover the high view of the church as Christ’s body, governed by His Word, sustained by His grace, and reformed continually by His Spirit. The ecclesia reformata semper reformanda—“the church reformed and always reforming”—is not a slogan of progressivism, but a commitment to ongoing repentance and fidelity to Scripture.

IV. Calvin and the Dutch Reformed Tradition

Though John Calvin never stepped foot in the Netherlands, his theological vision became the bedrock of Dutch Reformed Christianity for generations. His influence in the Low Countries was not merely intellectual—it was deeply ecclesiastical, political, and spiritual. Through his writings, students, and the spread of Reformed confessions, Calvin’s theology shaped the identity of a people who would become known for their commitment to doctrinal clarity, personal piety, and confessional fidelity.

The Dutch Reformation, like other Protestant movements, began as a response to the theological and moral corruption of the medieval church. But while Lutheranism made early inroads, it was Calvinism that ultimately captured the Dutch heart. What drew the Dutch to Calvin’s thought was not just his doctrine of predestination or his critique of Rome, but his robust vision of God’s sovereignty over every sphere of life—a vision particularly compelling in a nation struggling for religious and political freedom under Catholic Spain.

Calvin’s Geneva Academy played a pivotal role in training future Dutch ministers and theologians. Students such as Zacharias Ursinus, Caspar Olevianus, and Franciscus Junius carried Calvin’s theology back to the Netherlands, where they became instrumental in shaping the early Reformed churches. The Dutch quickly developed their own expressions of Calvinistic thought, culminating in the Three Forms of Unity: the Belgic Confession (1561), the Heidelberg Catechism (1563), and the Canons of Dort (1619). Each of these documents bears the clear imprint of Calvin’s theology—especially in its view of Scripture, the church, human depravity, and divine election.

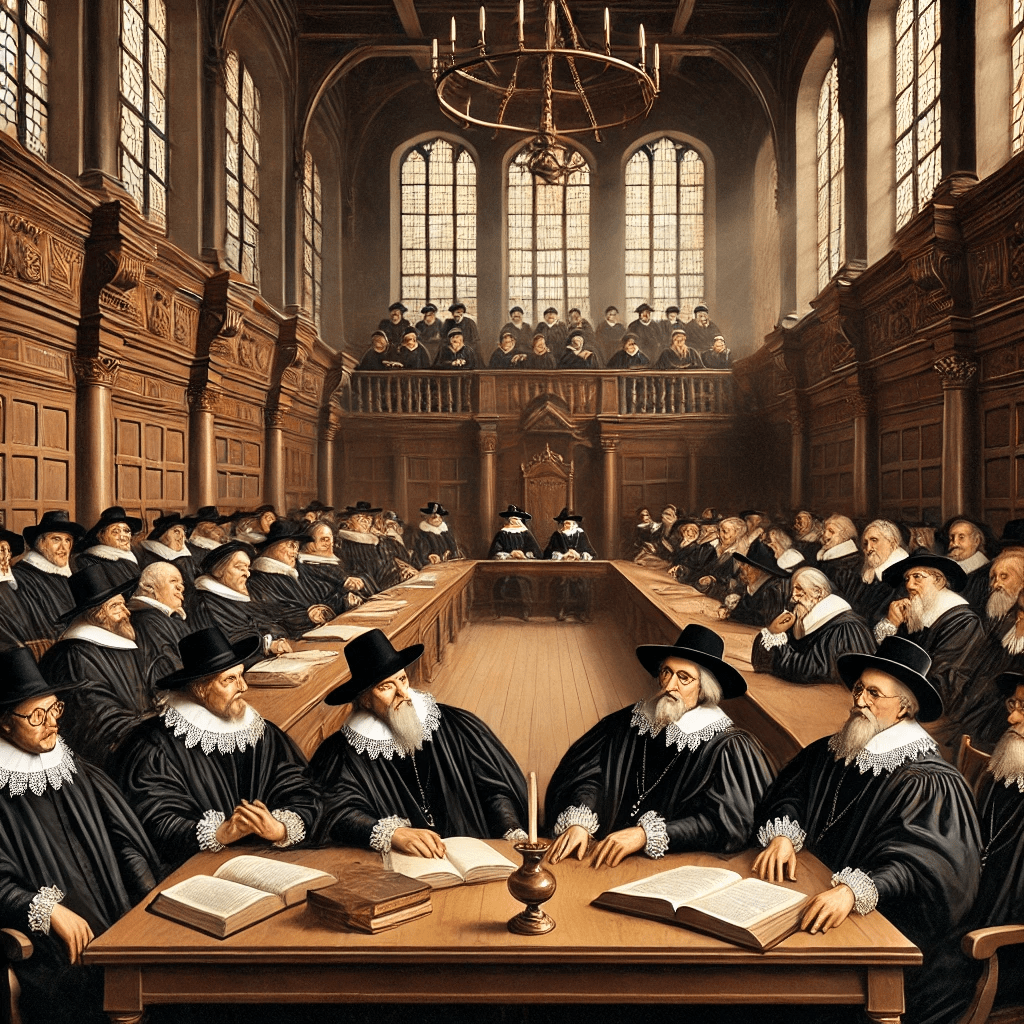

The most defining moment of Calvin’s impact in the Netherlands came with the Synod of Dort (1618–1619). This international Reformed council was convened to respond to the rise of Arminianism, a movement that challenged Calvin’s teachings on grace and predestination. The Synod reaffirmed the doctrines Calvin championed, particularly unconditional election, limited atonement, and irresistible grace—forming what would later be remembered as the Five Points of Calvinism or TULIP.

Although Calvin never systematized his theology into five points, his Institutes contain the heart of these doctrines. Regarding election, he wrote:

“We say, then, that Scripture clearly proves this much, that God by his eternal and immutable counsel determined once for all those whom he would one day admit to salvation, and those whom he would condemn to destruction.” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 3.21.7)

Calvin did not present election as a cold decree, but as a source of assurance and worship. He emphasized that election is rooted not in human worthiness but solely in God’s mercy and purpose:

“If we are elected in Christ, we shall find in him the assurance of our election.” (Battles ed., Institutes, 3.24.5)

The Dutch Reformed churches adopted this Christ-centered understanding of predestination, maintaining a strong sense of God’s covenant love and the believer’s security in Christ.

Calvin’s influence also extended to church polity and liturgy in the Netherlands. Dutch Reformed churches followed a Presbyterian model of governance, with ministers and elders sharing responsibility in consistories. Worship services centered on preaching, prayer, psalm singing, and the sacraments—echoing Calvin’s desire for simplicity and biblical faithfulness. “God disapproves all modes of worship not expressly sanctioned by his Word,” Calvin warned (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 4.10.23). The Dutch heeded that warning, developing a liturgy that was reverent, didactic, and saturated with Scripture.

Calvin’s understanding of the Christian life also resonated with the Dutch. His call to live “coram Deo”—before the face of God—was not confined to the church pew but extended into the home, the marketplace, and the government. This worldview would later give rise to a distinctively Reformed cultural vision championed by Dutch theologians like Abraham Kuyper, who famously declared, “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, ‘Mine!’”

In Calvin’s words:

“The Lord bids each one of us in all life’s actions to look to his calling. For he knows with what great unrest the human mind is borne hither and thither… So that no one may thoughtlessly transgress his limits, he has named these various kinds of living ‘callings.’” (Battles ed., Institutes, 3.10.6)

This doctrine of vocation—rooted in Calvin’s theology—took deep root in the Netherlands, producing generations of believers committed to faithfulness in both church and society.

Today, Dutch Reformed theology continues to shape churches across the world, from the Netherlands to South Africa, from Canada to the United States. While the landscape of Reformed churches has diversified, the DNA of Calvin’s Geneva remains unmistakable. His vision for a church under the Word, a life lived before God, and a kingdom extending into every area of life continues to animate and guide faithful believers across the centuries.

V. Calvin’s Spiritual Legacy Among the English Puritans and Scottish Presbyterians

Though John Calvin’s ministry was rooted in Geneva, his influence surged beyond the borders of continental Europe—especially into England, Scotland, and eventually America. The English Puritans and the Scottish Presbyterians adopted and adapted Calvin’s theology, shaping movements that would impact the course of Christian history for centuries. In them, Calvin found not only eager readers but spiritual heirs—men and women who embraced his theology of God’s sovereignty, covenantal worship, and a life lived under the lordship of Christ.

Calvin’s relationship to the English Reformation was both direct and providential. During the reign of Mary I (“Bloody Mary”), many English Protestants fled persecution and found refuge in Geneva. These Marian exiles—including John Knox and others—were exposed firsthand to Calvin’s ecclesiastical reforms and theological writings. When they returned to England under Elizabeth I, they brought with them not just ideas, but a vision: a purified church governed by the Word of God alone.

The Puritans, as they came to be known, were not a monolith but a movement marked by zeal for biblical fidelity. They longed to see the Church of England further reformed in worship, doctrine, and discipline. Calvin’s Institutes provided them with a comprehensive theological framework rooted in Scripture and aimed at producing a godly people. His doctrine of total depravity, effectual calling, and covenantal obedience were all embraced and preached from English pulpits. One Puritan minister declared that the Institutes was the “greatest work written since the days of the apostles.”

Calvin’s understanding of the Christian life as one of ongoing repentance and sanctification resonated with Puritan spirituality. He wrote:

“The whole life of Christians ought to be a sort of practice of godliness.” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 3.6.5)

The Puritans adopted this ethos wholeheartedly, emphasizing family worship, Sabbath observance, self-examination, and spiritual disciplines—not as legalism, but as the outworking of a regenerate heart. The Puritan mind, while scholastic in training, was deeply pastoral. They sought what Calvin called the experientia of grace—the lived experience of Christ’s sanctifying work through Word and Spirit.

In Scotland, Calvin’s legacy was most visibly realized through John Knox, a fiery reformer who spent time in Geneva under Calvin’s tutelage. Knox called Geneva “the most perfect school of Christ that ever was on the earth since the days of the apostles.” Upon returning to Scotland, Knox helped establish a national church modeled closely after Calvin’s vision: eldership rule, simple liturgy, expository preaching, and a high view of God’s sovereign grace.

This gave birth to Scottish Presbyterianism, which enshrined many of Calvin’s principles into enduring institutional forms. The First Book of Discipline (1560) and the Second Book of Discipline (1578) reflected Calvin’s influence in church polity and doctrine. But perhaps the fullest flowering came in the Westminster Assembly (1643–1653), where English and Scottish theologians crafted the Westminster Confession of Faith—a document deeply Calvinistic in tone and structure.

Calvin’s theology of God’s sovereign grace was at the heart of Westminster’s statements on predestination, justification, sanctification, and perseverance. The Assembly echoed his understanding that salvation is entirely by divine mercy:

“As Scripture, when it speaks of our free election, removes all merit on our part, so it enjoins humility, and deprives man of all pretext for glorying.” (Battles ed., Institutes, 3.21.2)

The English Puritans and Scottish Presbyterians did not worship Calvin. But they saw in him a guide—a shepherd-theologian who had faithfully taught the Word of God and called the church to holiness. They passed his theology on to future generations, including the American Puritans, who planted Calvinistic doctrine deep into the soil of New England. Preachers like Jonathan Edwards carried the torch forward, preaching the majesty of God and the weight of eternal things with Calvin’s deep sense of reverence.

Even today, Calvin’s fingerprints are visible in Reformed confessions, Presbyterian polity, and Reformed seminaries across the world. Wherever Christ is preached with awe, and the Scriptures are held in highest esteem, Calvin’s legacy quietly endures. As he wrote near the end of his Institutes:

“Let us not cease to do the utmost, that we may incessantly go forward in the way of the Lord… until we shall at length arrive at the goal.” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 3.6.5)

Calvin never desired to be known as a reformer, but as a humble servant of the Word. And in the Puritans and Presbyterians, we see the fruit of that humble obedience—a church reformed by the Scriptures and aflame with a passion for the glory of God.

VI. Calvin’s Broader Cultural and Ecumenical Impact

John Calvin is best known as a theologian of grace and a reformer of the church, but his impact reaches far beyond the pulpit or the seminary. His influence has permeated realms as varied as education, politics, economic theory, and global Christianity. He was a man of the Word, to be sure—but his vision of God’s sovereignty over all of life made him a forerunner of what we now call a Christian worldview. Calvin believed that all creation belongs to God, and that every domain of human endeavor must come under Christ’s lordship. In this way, his legacy is not only ecclesial but cultural—and not only Reformed but ecumenical.

Calvin’s doctrine of providence undergirded his view of the world as an ordered, purposeful creation governed by God’s sovereign hand. He wrote:

“The Lord has so knit together the order of the world, that nothing can be done without his will or permission.” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 1.16.6)

Far from promoting fatalism, this conviction gave Calvin confidence that every part of life—science, labor, law, and art—had meaning under the reign of Christ. This notion would later fuel Protestant work ethic theories, particularly in sociologist Max Weber’s famous thesis that Calvinism contributed to the rise of capitalism by dignifying secular work as a calling (Beruf).

But Calvin was not an economist; he was a pastor and theologian who saw all of life as “coram Deo”—before the face of God. In this light, work, study, and civic duty were all to be performed with reverence and responsibility. He declared:

“The Lord bids each one of us in all life’s actions to look to his calling… so that no one may thoughtlessly transgress his limits.” (Battles ed., Institutes, 3.10.6)

This doctrine of vocation elevated the ordinary. Calvin taught that the farmer behind his plow and the magistrate behind his desk both served Christ as meaningfully as the preacher in his pulpit, provided they acted in faith and obedience.

Calvin also placed a strong emphasis on education, founding the Geneva Academy in 1559 to train both ministers and lay leaders in the Word of God. Literacy was central, since the people of God needed to read Scripture for themselves. This emphasis helped usher in a culture of learning and critical thinking across Protestant Europe. In time, Reformed schools, universities, and seminaries were established throughout the world—from Princeton and Yale in America to Stellenbosch in South Africa.

In terms of politics, Calvin’s legacy is complex but significant. He was not a champion of popular sovereignty, but his insistence that all human authority is derived from God and accountable to Him laid the theological groundwork for resistance to tyranny and the rise of constitutional governance. Calvin insisted:

“We are subject to the men who rule over us, but only in the Lord; if they command anything against Him, let us not pay the least regard to it.” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 4.20.32)

This principle—known as the doctrine of lesser magistrates—was later employed by Reformed resistance movements across Europe and helped influence early American political thought, particularly among Calvinist dissenters.

Perhaps most surprisingly, Calvin’s influence reaches into ecumenical Christianity as well. Though his theology was distinctively Reformed, his emphasis on Scripture, grace, and the majesty of God has resonated with Christians from diverse traditions. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Calvin has been read not only by Presbyterians and Dutch Reformed churches, but by Baptists, Anglicans, Methodists, and even Roman Catholics. The rise of evangelical Calvinism in recent decades—seen in the ministries of figures like J.I. Packer, R.C. Sproul, and John Piper—demonstrates that Calvin’s voice still speaks powerfully to a global audience hungry for doctrinal depth and spiritual integrity.

Moreover, many Reformed churches in the Global South—particularly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America—trace their theological lineage to Calvin, either through missionary influence or indigenous adoption. These churches are now among the fastest-growing segments of the global church. In 2010, more than 80 million believers belonged to the World Communion of Reformed Churches, a testimony to Calvin’s global reach.

And yet, Calvin himself would be the last to seek credit. He labored not to exalt his name, but to exalt the name of Christ. As he wrote:

“We should consider that the principal end of our lives is to be so reconciled to God, and to devote ourselves wholly to him, that his glory may shine forth in us.” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 3.6.6)

In every generation, Calvin calls the church back to God-centered worship, grace-filled theology, and lives lived for the glory of Christ in every sphere. That is why, even five centuries later, his vision continues to inspire and shape the global church—ever reformed, ever reforming.

VII. Why We Still Need John Calvin

In an age defined by theological confusion, spiritual consumerism, and institutional instability, the life and legacy of John Calvin remain remarkably relevant. Born over five hundred years ago, Calvin was not interested in novelty, popularity, or building a personal brand. He was captivated by the majesty of God, the authority of Scripture, and the glory of Christ in the church. And he labored—quietly, often painfully—for the rest of his life so that the truth of God might reign in the hearts of His people. Today, we still need John Calvin—not because he was perfect, but because he was faithful.

Calvin reminds us that theology is not a mere intellectual exercise but a matter of life and death. He begins his Institutes by showing that true wisdom begins with knowing God and knowing oneself rightly:

“Our wisdom, in so far as it ought to be deemed true and solid wisdom, consists almost entirely of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves.” (Battles ed., Institutes, 1.1.1)

In an age obsessed with self-expression and self-fulfillment, Calvin redirects our gaze upward. We are not autonomous individuals floating in a meaningless cosmos; we are creatures made by a holy God, corrupted by sin, and in need of redemption. The recovery of this twofold knowledge—of God’s majesty and man’s misery—is as vital today as it was in Calvin’s time.

Calvin also reminds us that the church matters. In a world where church attendance is declining and institutional distrust is on the rise, Calvin’s robust vision of the visible church stands as a countercultural testimony. The church, he insists, is the mother of believers, the household of faith, and the place where God nourishes His people:

“There is no other way to enter into life unless she [the church] conceive us in her womb, give us birth, nourish us at her breast, and lastly…keep us under her care and guidance.” (Battles ed., Institutes, 4.1.4)

His commitment to preaching, sacraments, discipline, and godly leadership is not about control but care—about forming a people devoted to God and conformed to Christ.

Perhaps most importantly, Calvin reminds us of the supremacy of God’s grace. In his view, salvation is not the result of our striving or achievements but the free mercy of a sovereign God. This was not cold fatalism—it was the burning center of Christian assurance and joy. “We are elected in Christ,” Calvin wrote, “and we shall find in him the assurance of our election” (Battles ed., Institutes, 3.24.5). Far from producing arrogance, this truth should lead to humility and worship. As Calvin put it:

“Let us not be ashamed to be ignorant in something, or not to succeed in everything. Let us be content to be learners in Christ’s school until the end.” (Beveridge ed., Institutes, Prefatory Address)

This is why Calvin’s legacy lives on. He did not set out to build a movement; he sought only to be faithful to the Word of God. Yet his vision reshaped nations, emboldened reformers, instructed generations of believers, and gave the church a theological foundation that still stands today.

Calvin’s personal motto, which he used in correspondence and had engraved in his heart, was this:

“Cor meum tibi offero, Domine, prompte et sincere”—“I offer my heart to you, O Lord, promptly and sincerely.”

That is a fitting summary of his life. Not self-centered ambition, but joyful surrender. Not innovation for its own sake, but faithfulness to God’s Word. Calvin’s enduring relevance is found not in the age of his books, but in the timelessness of the truth he taught. And though he is often caricatured as austere or severe, those who read him with care will discover a man full of pastoral tenderness and spiritual insight.

So on this July 10th, let us remember John Calvin not as a distant relic of the past, but as a gift of Christ to His church. Let his words reawaken our awe of God. Let his vision rekindle our love for Scripture. Let his example encourage us to live sincerely, courageously, and reverently—before the face of God, in the power of His grace, and for the glory of His name.

“For since we are not our own, in so far as we can, let us forget ourselves and all that is ours.”

—John Calvin (Beveridge ed., Institutes, 3.7.1)

Soli Deo Gloria.